The Lincoln Charter Project

Analyses of Henry III 1272 Charter

Delmina Barros| June 13, 2021

The Charter Project

The beginning In 2018, a rare collection of royal charters was restored as part of a project to conserve precious documents for future generations. This project was created between the University of Lincoln (UK) and the City of Lincoln Council, where conservators and experts digitally record, preserve, and analyse some of the city’s manuscripts. The collection of royal charters belonging to Lincoln included many essential documents with 400 years from 25 kings (from King John, Richards II and Henry V). These documents were analysed and restored for the first time since 1788 (Beirne R. 2019/20).

Currently, Together with the City of Lincoln Council, the Conservation Department at the University of Lincoln (UK) continued working together with the collection of historical royal charters. In addition, the MA students in Conservation of Cultural Heritage worked in groups with a research project into the Lincoln city charters. The project encouraged using some digital heritage technologies to gather evidence into the condition of the charter allocated to each group.

With the objectives of this project in mind, we aimed to:

- Reveal as much information as possible about the charters, using the technologies available

- Suggest ways to disseminate the research findings to project stakeholders in the appropriate format(s)

- Contribute to the custodians’ objectives for the project (above).

This project required non-destructive techniques (those that do no damage the material under analysis, but they may require a sample to be removed from the object) and non-invasive techniques (those which do not require a sample to be removed from the object, and which leave the object in its essentially the same state before and after analysis) (Adriaens 2005) and analytical techniques.

Analyses of the Object

The Charters of Lincoln are a group of public documents branching several centuries, each issued by the monarch of the day to confer certain rights and privileges upon the city’s citizens. The text of the Charters of Lincoln is of great historical importance and has long been recognized.

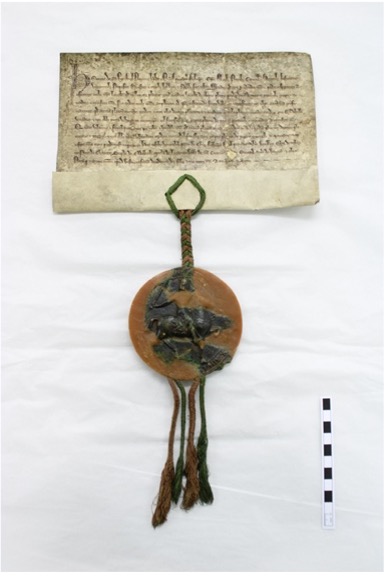

Materials and manufacture The charter is constituted by the parchment (where the message is written, the seal and the thread that attaches the royal seal to the parchment (see figure 1 above)(Beirne R. 2019/20)

Parchment Parchment, a writing material made from prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. In order to make the parchment more aesthetically pleasing or more suitable for the scribes, unique treatments were used, like powders and pastes, to help remove grease so the ink would not run. (figure 2).

Available from: http://hrsbstaff.ednet.ns.ca/kmason/images/Illuminations1.pdf [assessed on the 05-05-21]

Parchment a material consists of collagen fibre, a 13% water content and 1.6% residual lime. Collagen bonds easily with water molecules, leaving parchment particularly sensitive to the presence of water. Therefore, it is vulnerable to a high or fluctuating RH, rapidly absorbing water in high humidity and losing it as the humidity is lowered. These changes cause the parchment to expand and contract, causing objects to become deformed (Woods 2006)(Beirne R. 2019/20)

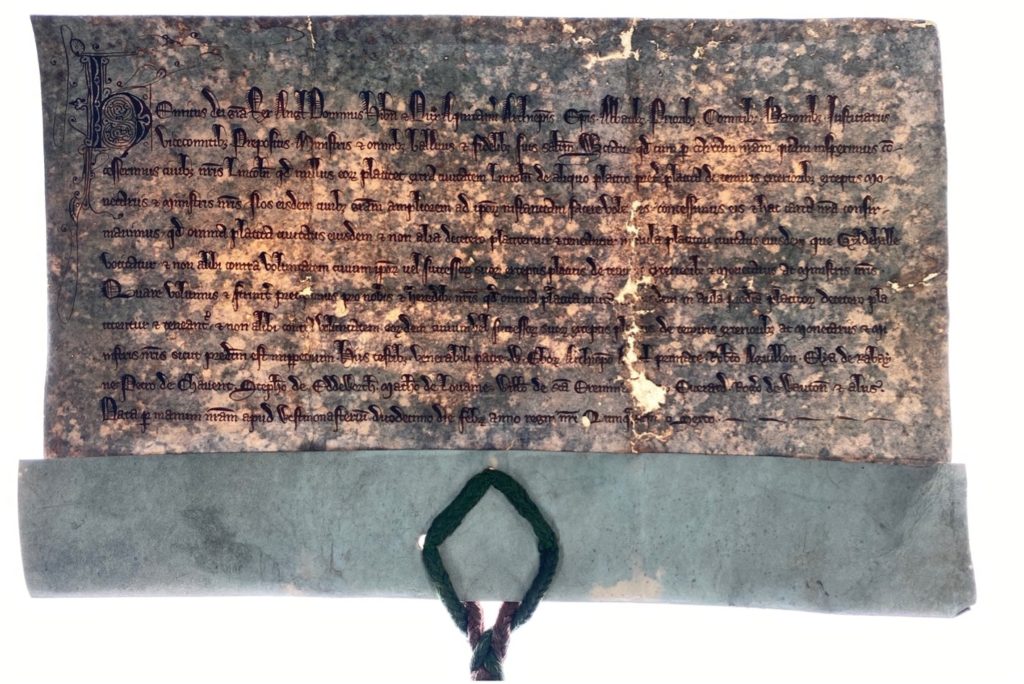

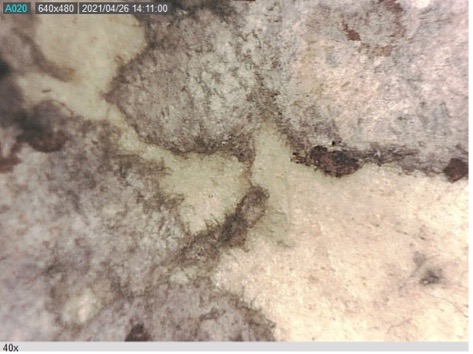

The parchment in this charter is in good condition, although on the surface suggests that it has been exposed to a fluctuating RH. The surface has become worn in some areas( see figure 3 and 4), with exposed corners being particularly vulnerable. It is also here where we see the most visible patches of ingrained dirt and discolouration, as particulates of dirt have become trapped in the creased surface(Beirne R. 2019/20).

Ink

The condition of the ink requires ongoing assessment. Ink cracks as the parchment swell and shrinks during RH fluctuations and can be quickly lost to flaking. Therefore, control points across the document should be photographed and monitored, with images compared each year. The risk of ink loss is heightened in the areas that are cockling and folding, where the parchment becomes distorted and creased (Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20).

There is an additional risk to the legibility of the document, with the iron gall ink itself liable to corrosion and causing damage to the parchment (The Iron Gall Ink Website 2020)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20). Fortunately, the charter shows little sign of damage in terms of the ink corroding through the parchment – iron gall ink can be stable over long periods, but conservators should be aware of the risks and the need to control the storage environment(Beirne R. 2019/20). Much of the charter’s original writing appears in good condition with minimal flaking (Beirne R. 2019/20) A Dino-Lite image taken with visible light showing the condition of the writing (see figure 5 below)

Condition Assessment

Overall the 1272 charter is in stable condition and in order not to deteriorate further, it needs to be kept in appropriate conditions. Transportation is cause for concern, and great potential for parchment, seal and cords to move independently causing damage, and the ink condition will require ongoing assessment as outlined above. However, despite some deterioration, the charter is mainly intact, there is no active corrosion from the iron gall ink, and the lettering remains legible(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20)

Preventive Conservation

It is important to establish controls for the storage environment, because of the vulnerabilities of each material. To conserve parchment, relative humidity (RH) should be maintained between 45 and 60% to avoid mould growth, and fluctuations in RH and temperature must be reduced to prevent dimensional changes. If on display, light levels should be kept below 50lux to reduce fading of pigments in the ink and textiles and filtered for UV (Woods 2006). While in storage, the charter should not be exposed to light and should be kept in custom packaging of buffered, acid-free cards to immobilise all elements during transportation, and handling should be minimised to lower the risk of accidental damage(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20)

Royal Seal

A seal attached to a document indicates one’s authorisation of the contents. At the time of the Charters drafting, it also functioned as evidence of the document’s authenticity as well as rendering its written terms unquestionable (Burns 1998)(Beirne R. 2019/20)

A seal attached to a document indicates the authorisation of the contents. At the time the Charters was created, it also functioned as evidence of the document’s authenticity as well as rendering its written terms unquestionable (Burns 1998)(Beirne R. 2019/20) The seal attached to the Charter by braided cords hanging down (see figure 2) the lower edge is one of the Great Seals of England, the symbol of the office of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. And when attached to a document represents the approval of the Sovereign of the day(Beirne R. 2019/20) The impression of the Seal wields great power and authority and, as a result, has always had two sides ( see figures 5 and 6), but also obliges the need for it to hang from documents so that both sides can be inspected, (Burns 1998)(Beirne R. 2019/20)

The 1272 Charter of Henry III is significant among the charters collection as it granted the citizens of Lincoln a legal place, the Guildhall, to make their pleas. A detailed examination of the Seal attached to the Charter and the cord used to secure it reveals some interesting details to our understanding of the document(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20)

The seal attached to this Charter is that of Henry III even though it is difficult to identify it as such because many of the original is missing. As per figures 6 and 7, the seal has been restored as most of it had been damaged and lost.

Several studies of medieval English wax seals have revealed that they usually consist of only beeswax Young et al., 1987)(Beirne R. 2019/20) In these same studies, it was noted that while there was very little chemical change to the waxes compared with later resin compositions, the soft nature of the beeswax had resulted in physical alterations and damage to some seals(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20) The repairs may have been carried out in this distinctly noticeable manner (see figure 6 and 7) (figure 8and 9) because attempting to replicate the original colour and design could have been interpreted by later generations as an attempt of forgery or questioned the legitimacy of the charter. By making all repairs distinguishable from the original seal, the legal integrity of the seal has been maintained (Burns 1998)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20)

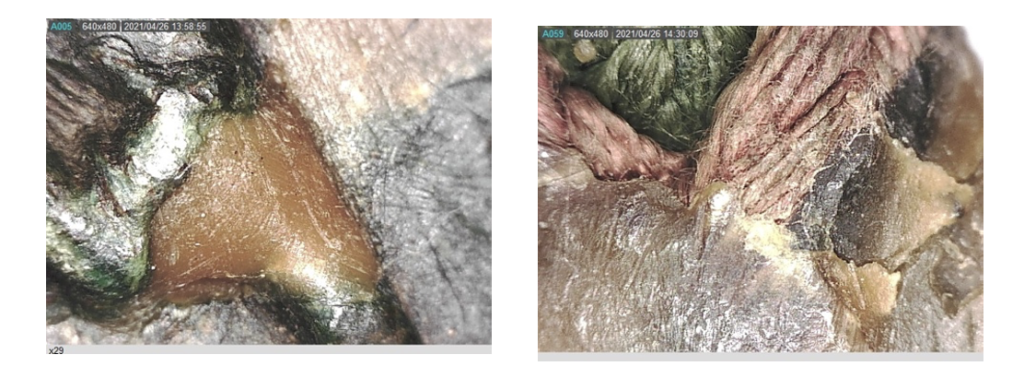

The seal shows no signs of biological attack and does not appear to be in immediate danger of deterioration, but requires careful handling due to the nature of the material(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20). Although the cords appear intact there are numerous breakages of individual threads when examined using a Dino-Lite ( see figures 10 and 11 below), which is a sign of deterioration.

Experimental testing of historic silk fibres suggests that high temperature and RH accelerates deterioration (Luxford et al. 2019), and as previously mentioned, should be stored in a controlled environment with minimal handling in order to avoid placing mechanical stress on the threads(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20).

Thread/Cords There are different methods used to attach a Seal to a document.

Having said that, the three-eyelet lace method used in this charter (see figure 12) was one of the most elaborate. The Royal Chancery was often used in medieval times to represent the greater importance of royal documents intended for perpetual use, such as a charter, compared to documents that were of temporary value, such as letter patents or letters close (Dalton 1992)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20). Making this method more robust than the other sealing methods, to ensure the documents survival. The bottom of the parchment underneath the writing is folded over to create a double thickness, called a plica (Burns 1998), from which to suspend the wax seal (Maxwell-Lyte 1926)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20)

The two cords, usually braided in different colours, are threaded through the eyelets in the sequence demonstrated in figure 12, after which the seal is affixed to the cord in the method described below (Burns 1998) (Beirne R. 2019/20). Both coloured laces are individually braided using a finger loop method(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20).

Following the threading of these individual laces through the parchment eyelets, as mentioned above, the two laces become four and are braided together and tied at the end with a knot (Dalton 1992) (Beirne R. 2019/20). The braid would have been placed between two layers of warm wax with its end passing through its bottom. The layers of wax were fused into one by pressing them between the two sides of the silver seal matrix, the metal mould which creates the seal impression (Burns 1998) (see figures 13 and 14)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20)

When attached to documents, the orientation of the Great Seal was quite specific; the head of the sovereign had to be perpendicular to the writing on the parchment on both sides of the seal. On the front of the seal, the side facing upwards with the document’s text represents the sovereign enthroned, while on the reverse, they are displayed heading the military or naval forces, usually astride a horse (Maxwell-Lyte 1926)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20).

The cords used to affix the seal are green and pink (see figures 13 and 14). Green and red are noted as a popular choice (Maxwell-Lyte 1926), and it is possible that the pink cord of this Charter was originally a red that has now faded from photodegradation(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20).

Other features of the Charter such as the method of sealing and the colour of the wax used have specific administrative significance, it is purported that the colour of the laces used to attach the Great Seal was completely arbitrary, though the use of two different colours did seem to be a standard feature, (Maxwell Lyte 1926)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20).

In this case, the royal seal appears to have been attached incorrectly, possibly done by mistake during the previous restoration (see figure 15 and 16 below).

Digital Recording Techniques

The investigation into an object requires detailed records to enable current and future researchers and conservators the continuing examination without handling the artefact.

Photography

Photographs give details of an object’s form. In the photographs produced, we can identify the charter’s features and divide it in three main material components – the parchment(with many details in the writing), the silk cords and wax seal( see figures 14 and 15)(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21](Beirne R. 2019/20).

By using digital recording techniques, like RTI and Photogrammetry, different structural differences will be captured in comparison to regular photographs(Investigating the Lincoln Charters. Available from: https://mairtrueman.wixsite.com/thechartersproject [assessed 11-06-21] (Beirne R. 2019/20).

Ultraviolet (UV) photograph

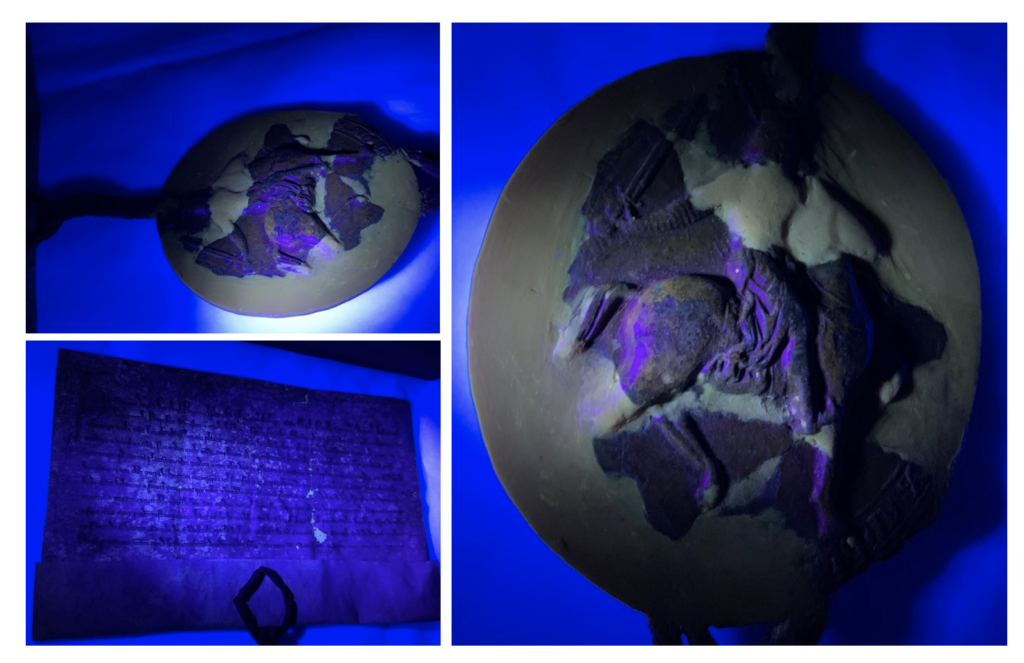

UV analyses helps identify previous restoration by highlighting the areas retouched in a darker purple hue, and in this case, there were a couple of areas that showed the previous retouching (figures 17, 18 and 19 below).

This analysis shows a possible retouching in the seal area, highlighted in dark purple (see figure 19 left). The parchment did not show sign of the previous retouch but highlighted the tear mending previously done see figure 18).

X-ray (radiography): Imaging technique to view the internal structure of an object and it is:

- Non-destructive

- Traditionally used for metals, but with the right settings, it can be possible to see textiles (stitching and weave of fabrics), wood, certain pigments, ceramics, bone.

- The size of the x-ray cabinet available limits the size of objects for study available.

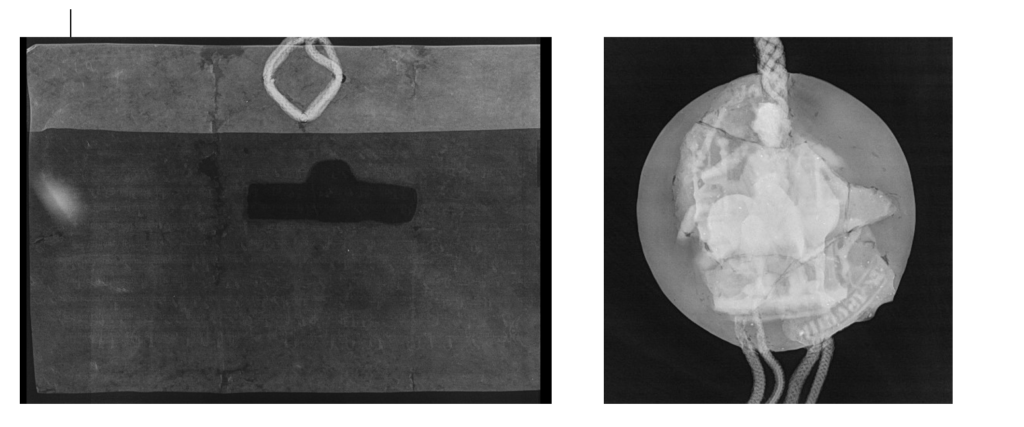

An x- ray of the seal revealed the mechanics of the repairs; in figure 20 (on the left), the parchment part of the charter did not show any hidden structure condition. On the other hand, the x-ray done on the seal (figure 21 on the right) showed possible internal cracks and enhanced the previously restored areas.

Infra-red photography

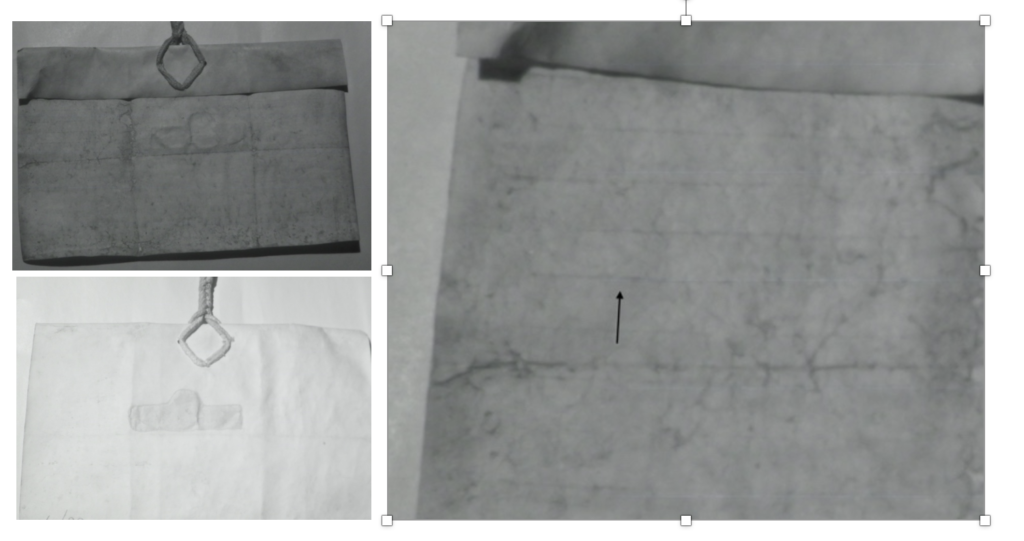

Infrared imaging helps identify any underdrawings as part of the artist drawing and preparation.

Under infra-red photographs it was revealed the underlines place in the parchment before writing (figure 24 top right) .

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF): a technique for elemental and chemical analysis

This analyses is:

- Non destructive

- Surface technique

- Elemental composition

- Identification of inorganic composition (metals, ceramics, glass, stone, mortar, inorganic pigments)

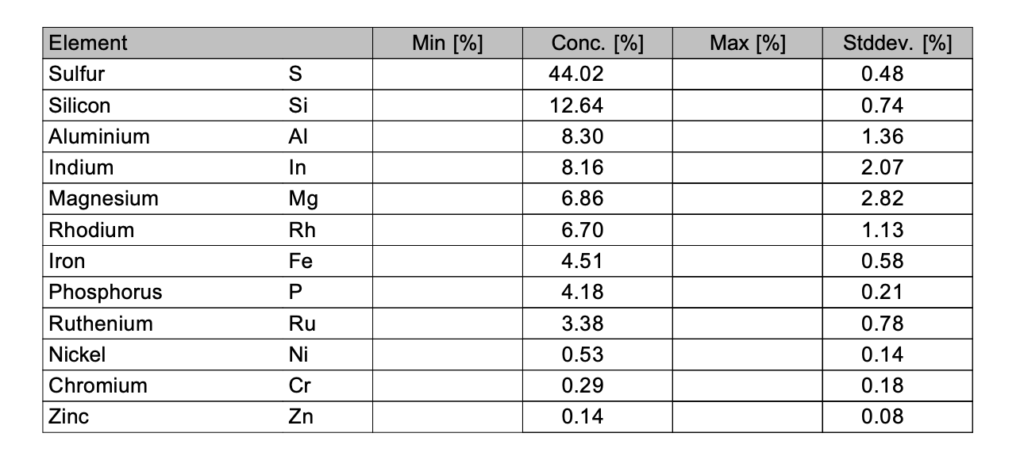

Tests were made in the charter’s ink, and the XRF results are consistent with iron gall ink, with high concentrations (Conc. [%] in the table below) of sulphur (44.02%) and iron (12.64%) (see figure 25 below).

Ink

Iron gall ink has been used since the 5th Century AD up to the 20th Century. Whic makes it reasonably to expect its use on a 13th Century document, and the charter’s XRF results support this prediction.

Iron Gall Ink Production: There are many iron gall ink recipes. However, four primary ingredients remain constant: tannin, vitriol (iron sulphate), Gum Arabic and water. Tannin was extracted from tree galls (a growth resulting from insect larvae hatching within tree bark). In contrast, vitriol could be extracted from mines or obtained as a byproduct of alum manufacturing (often contaminating the ink with aluminium), and Gum Arabic was taken from Acacia trees. A range of other ingredients could be added to alter the ink’s properties, such as indigo to change the colour or brandy to prevent it from freezing. Generally, manufacture consisted of crushing tree galls and combining this with liquid vitriol and Gum Arabic (The Iron Gall Ink Website 2020).

Digital Techniques

RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging)

The use of computer software, revealing an object’s surface shape and distortions.

For RTI, by the combination of a series of photographs, each lit from a different angle (Cultural Heritage Imaging 2020).

This process allows the re-light of the charter from any direction, picking out details that are easier seen under raking light, particularly the condition of the parchment, folds and creases in its surface, and how these folds would have been layered when closed (see figure 25). Another feature of RTI is the Normals Visualisation, which gives a false-colour version of the object, highlighting the seal’s contours (see figure 26).

This method is:

- Non-invasive re-coding method (non-contact)

- Surface texture is captured

- It uses a series of digital photographs under various light angles

- Access to RTIBuilder software is required to process the image

Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry software aligns several overlapping photographs, with the camera rotated around the object for each photograph, reconstructing the object’s 3D measurements to produce an interactive model (Cultural Heritage Imaging 2020). The textural information captured through this technique is less detailed than the ones previously mentioned, but it has the advantage of enabling the viewer to circle the virtual model as they would a physical artefact. This technique is beneficial for this charter has it highlights the depth of features impressed into the wax seal, lending more solidity to the object and depicted figures (see figures 27 and 28).

This technique is:

- Non-invasive method (non-contact)

- Used as a documentation and recording technique

- It uses a series of digital photographs – the camera is moving around the imaging subject

- A textured 3D model is generated

- Access to photogrammetry software is required to process the images

Additional Resources

For more information on the topics discussed, please see the resources referenced here:

Adriaens A. (2005), Non-destructive analysis and testing of museum objects: An overview of 5 years of research. Gent Univerity. Available from: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/329834/file/563160.pdf [assessed 23-05-21]

Belcher, S. (2018), Rare Collection of Royal Charters to Be Preserved for Future Generations. [online] Available from: <https://www.lincoln.ac.uk/news/2018/02/1440.asp> [Accessed 17/05/2021]

Bezur, A. et al. (2020), Handheld XRF in Cultural Heritage: A Practical Workbook for Conservators. Getty Conservation Institute.

Beirne R., 2019/20. Multimedia Presentation/Digital Object ‘In Closer Detail:The 1456 Henry VI Lincoln Charter Seal’

Birch, Walter de Gray (1911), The Royal Charters of the City of Lincoln, Henry II to William III. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Burns, T. C. (1998), ‘Studies in Documents : The Royal Proclamation

Charter for the Company of Adventurers’, Archivaria 45, Spring, pages 170–193. accessed on 12/04/2020, available from: <https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12230/13255> [assessed 03-05-21]

Cambridge University Press (2010), ‘Cambridge Library Collection’, The Royal Charters of the City of Lincoln : Henry II to William III, Cambridge University Press, New York. Available from: <https://www.cambridge.org/ie/academic/subjects/law/legal- history/royal-charters-city-lincoln-henry-ii-william-iii?format=PB> [assessed 05-05-21]

Crowfoot, E., Pritchard, F. & Staniland, K. (2006,) Textiles and Clothing, c.1150 – c.1450. Medieval Finds from Excavations in London, 4 (2nd edition), The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. Available from: <https://books.google.ie/books?id=CY- 8T59wHHUC&pg=PA15&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false> [assessed 05-05-21]

Cultural Heritage Imaging (2020), Technologies. [online] Available from: <http://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/Overview/index.html> [assessed 05-05-21]

Dalton, J. P. (1992), The Archiepiscopal and Deputed Seals of York : 1114 – 1500, Borthwick Publications, University of York. Available from: <https://books.google.ie/books?id=3- HfVy7wVfcC&pg=PA17&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false> [assessed 05-05-21]

De Gray Birch, W. (1911), The Royal Charters of the City of Lincoln : Henry II to William III., Cambridge University Press, London. Available from: <https://archive.org/details/royalchartersofc00lincrich/page/102/mode/2up/search/1456> [assessed 05-05-21]

Duff, D. G & Sinclair R. S. (1977), ‘Light induced colour changes of natural dies’, Studies in Conservation, 22:4, p161 – 169. Available from: < https://www-jstor- org.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/stable/1505832> [assessed 08-05-21]

Fleetwood, G. & Jorgenson, M. (1949), ‘The Conservation of Medieval Seals in the Swedish Riksarkiv’,The American Archivist, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Apr), pg.166-174. Available from: < https://www.jstor.org/stable/40288737> [assessed 05-05-21]

Fowlers, R. C. (1925), ‘IV.—Seals in the Public Record Office’, Archaeologia or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity, Second Series, Vol.74, p.103-116. Available from: <http://ignca.gov.in/Asi_data/24487.pdf> [assessed 09-05-21]

Gilroy, C. G. (1845), The History of Silk, Cotton, Linen, Wool and Other Fibrous Substances, Harper & Brothers, New York. Available from: <https://books.google.ie/books?id=U6BCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA390&lpg=PA390&dq=linen+polishi ng+silk like&source=bl&ots=NhcJaxw1WM&sig=ACfU3U0yF10t4d9QlKRmiczyB5GN20cdOA&hl=en&s a=X&ved=2ahUKEwilqOHTru3oAhWyunEKHZ- cA7IQ6AEwE3oECA0QKQ#v=onepage&q=linen%20polishing%20silk-like&f=false [assessed 05-05-21]

Hacke, A. -M, Carr, C. M. & Brown, A. (2004), ‘Characterisation of metal threads in Renaissance tapestries’, Proceedings of Metal 2004, National Museum of Australia, Canberra ACT 4–8 October 2004. Available from: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228353577_Characterisation_of_metal_threads_in_ Renaissance_tapestries> [assessed 05-05-21]

Haines, B.M. (2006), ‘The Manufacture of Parchment.’ In Kite, M. and Thompson, R. (eds). 2006. Conservation of Leather and Related Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam and Boston.

Huang, A. l. & Jahnke, C. (2015), Textiles and the Medieval Economy : Production, Trade, and Consumption of Textiles, 8th–16th Centuries. Oxbow Books. Available at <https://eds-b-ebscohost- com.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzk2NzUxN19fQU41?sid=923 03224-e533-4990-ba01-447adb9018e7@pdc-v- sessmgr02&vid=0&format=EB&lpid=lp_104&rid=0> [assessed 05-05-21]

Jayne, E. (2016), Seals and sealing: An introduction to seals through the archives of the Norfolk Record Office, Norfolk Record Office Blog, August 19. Available from: <https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2016/08/19/seals-and-sealing-an-introduction-to-seals- through-the-archives-of-the-norfolk-record-office/> [assessed 05-05-21]

Mairinger, F. 2004. UV-, IR-, and X-ray imaging. In Janssens, K. and Van Grieken, R. (eds). 2004. Non-Destructive Micro Analysis of Cultural Heritage Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam and Boston.

Mathews, K. (2018) Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Textile Terms: Four Volume Set, Woodhead Publishing India PVT Ltd, New Delhi. Available from: <https://books.google.ie/books?id=XkqoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA679&lpg=PA679&dq=dictionary+of +textile+terms+glaze&source=bl&ots=1eL6G9c- Ej&sig=ACfU3U1nrTBdmRqdnh4I8P0VSMtKJ_5rEA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjB4Znpnu_o AhUUUBUIHe_8DZ8Q6AEwAHoECAcQKQ#v=onepage&q=dictionary%20of%20textile%20term s%20glaze&f=false> [assessed 10-05-21]

Maxwell-Lyte, Sir H. C. (1926), Historical Use of the Great Seal of England, H.M. Stationary Office, London. Available from: <https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008927983&view=1up&seq=17> [assessed 10-05-21]

McQuillan, K. (2015), Conservator’s eye view: wax seals : The Medieval Seals at St George’s Chapel Archives or a Geek’s blog, Dean and Canons of Windsor. Available from: <https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/conservators-eye-view-wax-seals/> [assessed 05-05-21]

Norton, E. (2018), ‘Medieval experts restore prized collection of royal Lincoln charters’, The Lincolnite, February 22. Available from: <https://thelincolnite.co.uk/2018/02/medieval-experts-restore-prized-collection-royal-lincoln- charters/> [assessed 10-05-21]

Nutz, B. (2014), ‘DRGENS SN WIR VS NVT SCHAME – NO SHAMEIN BRAIDING15TH CENTURY FINGERLOOP BRAIDS FROMLENGBERG CASTLE’, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 18: 2, pg.116–134. Available from: <https://www.academia.edu/8501549/DRGENS_SN_W IR_VS_NVT_SCHAME_ – _No_Shame_in_Braiding._15th_Century_Fingerloop_Braids_from_Lengberg_Castle._In_Estoni an_Journal_of_Archaeology_18_2_2014> [assessed 23-05-21]

Owen-Crocker, G. R. (2004), Dress in Anglo-Saxon England, Boydell Press, Suffolk. Available from: <https://books.google.ie/books?id=45RJYhTGZiUC&pg=PA281&lpg=PA281&dq=flax+distaff+en gland+medieval&ource=bl&ots=Rh3Xh3H3r6&sig=ACfU3U2dEgFjT4r-Ai_- xceOy9H0znoIPw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjf2bTD0O3oAhU5ZxUIHVIMAo8Q6AEwEXoEC A0QKQ#v=onepage&q=flax%20distaff%20england%20medieval&f=false> [assessed 05-05-21]

Oddy, W. A. (1977) ‘The Production of Gold Wire in Antiquity: Hand-Making Methods before the Introduction of the Draw-Plate’, Gold Bulletin 10: 3, p.79-87. Available from: <https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/BF03215438.pdf> [assessed 25-05-21]

Padfield, T. & Landi, S. (1966) ‘The light-fastness of the natural dyes’, Studies in Conservation, 11:4, Nov, pg.181 – 196. Available from: <https://www- jstor-org.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/stable/1505361?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents> [assessed 05-05-21]

Percival, M. (1912), Chats on Old Jewellery and Trinkets, T. Fisher Unwin, London. Available from: <https://jewelryexpert.com/articles/Pinchbeck.htm> [assessed 13-05-21]

Rammo, R. (2016), ‘SILK AS A LUXURY IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN TARTU (ESTONIA)’, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 20: 2, pg.165–183. Available from: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310663454_Silk_as_a_luxury_in_late_medieval_and _early_modern_Tartu_Estonia> [assessed 05-05-21]

Saul, N. 1997. Richard II. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Schweppe, H. (1979), ‘Identification of Dyes on Old Textiles’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Autumn), pg 14-23. Available from

< https://www-jstor-org.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/stable/3179569> [assessed 05-05-21]

Selwyn, L. (2017), Understanding how silver objects tarnish, Canadian Conservation Institute. Available from: <https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation- institute/services/workshops-conferences/regional-workshops-conservation/understanding- silver-tarnish.html> [assessed 12-05-21]

The British Library. 2013. Collection Care Blog: Here’s looking at you kid: Under the microscope with leather. Available from: <https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2013/09/heres-looking-at-you-kid-under-the-microscope-with-leather.html [assessed 05-05-21]

The Royal Charters of the City of Lincoln: Henry II to William III. Cambridge University Press. Available from:

The National Archives (2020), Seals. Available from: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/seals/ [assessed 03-05-21].

The Privy Council Office (2020), Royal Charters. Available from: https://privycouncil.independent.gov.uk/royal-charters/ [assessed 03-05-21].

Thompson, J.C. 1995. Manuscript Inks. The Caber Press.

Tímar-Balázsy, Á. & Eastop, D. (2011), Chemical Principles of Textile Conservation, Routledge, New York. Available from: <https://www-dawsonera- com.proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/readonline/9780080501048> [assessed 03-05-21].

Toth, M. (2013), ‘Lessons learned from conserving metal thread embroidery in

the Esterházy Collection, Budapest, Hungary’, Studies in Conservation, Volume 57, Issue sup1: 24th Biennial IIC Congress: The Decorative: Conservation and the Applied Arts, pg s305 – s312. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1179/2047058412Y.0000000056> [assessed 03-05-21].

Vodopivec, J. (1995), ‘The Preservation and Protection of Medieval Parchment Charters in Slovenia’. In IADA Preprints 95, ed. Mogens S. Koch and K. Jonas Palm (Copenhagen: Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, 1995)

Watteeuw, L. (2019) The Conservation of the Charters of the Old University of Leuven. Available from: https://theo.kuleuven.be/apps/press/bookheritagelab/tag/wax-seals-conservation/ [assessed 03-05-21].

Weiszburg, T. G et al. (2017), Medieval Gilding Technology of Historical Metal Threads Revealed by Electron Optical and Micro-Raman Spectroscopic Study of Focused Ion Beam- Milled Cross Sections, Analytical Chemistry, Sept, American Chemical Society. Available from: <https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01917> [assessed 03-05-21].

Woods, C.S. (2006), The Conservation of Parchment. In Kite, M. and Thompson, R. (eds). 2006. Conservation of Leather and Related Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam and Boston.

Wyon, A. B & Wyon, A. (1887), The great seals of England : from the earliest period to the present time : arranged and illustrated with descriptive and historical notes,

Elliot Stock, Chiswick Press, London. Available from: <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010430270> [assessed 03-05-21].